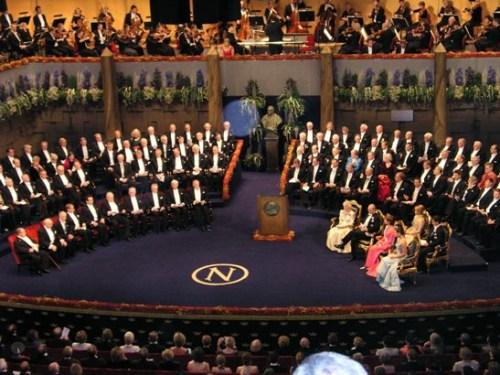

瑞典当地时间12月10日下午4点30分,2016年诺贝尔奖颁奖仪式在瑞典斯德哥尔摩音乐厅正式举行。文学奖得主鲍勃·迪伦因事未能出席。此前,鲍勃·迪伦已提前知会诺奖评委会,他会缺席这次领奖,而由有着“朋克教母”之称的美国女歌手、诗人帕蒂·史密斯代为领奖,并演唱鲍勃·迪伦1963年经典作品《大雨将至》。他的获奖感言由美国驻瑞典大使代为朗读。

以下为凤凰文化全文编译的鲍勃·迪伦获奖感言:

各位晚上好。 我向瑞典学院的成员和今晚出席宴会的所有尊贵的客人致以最热烈的问候。

很抱歉,我没能与你们在一起,但请知道,在精神上,我绝对与你们同在,很荣幸获得了这么一个有声望的奖。 被授予诺贝尔文学奖,是我从来不敢想象或预见到的事情。从小,我就熟悉、阅读并受益于那些被认为值得获得该项殊荣的人的作品:吉卜林、托马斯·曼、赛珍珠、加缪、海明威这些文学巨人总是给人深刻的印象,他们的作品在学校课堂上被教授,被收藏在世界各地的图书馆,被人们用虔诚的语调谈论着。现在我加入这样的名列,真的难以言说。

我不知道这些男人和女人们是否曾经想过自己能够获得诺贝尔文学奖,但我想,在这个世界的任何地方,任何写过一本书、一首诗、或是一部戏剧的人,在内心深处都会拥有这么一个秘密的梦想。这个梦想被埋藏得太深,他们甚至都不知道它在那里。

有人曾告诉我,我不可能获得诺贝尔奖,我也不得不认为这个几率与我站在月球上的几率相同。事实上,在我出生的那一年和随后的几年,世界上没有一个人被认为优秀得可以赢得诺贝尔奖。所以,我认为,至少可以说,我现在属于这个非常少数的群体。

收到这个令人惊讶的消息时,我正在路上。我花了好几分钟才确定它没错。我开始回想起威廉·莎士比亚这位伟大的文学人物。我估计他认为自己是一个剧作家。他正在写文学作品的这个想法不太可能进入他的脑子。他的文字是为舞台而写,是用来说的,而不是阅读的。当他在写《哈姆雷特》的时候,我确信他在思考很多不同的事情:“谁是这些角色的合适的演员? “这应该怎样演出来?”“我真的想把这场戏设置在丹麦吗?”他的创造性的想象与野心毫无疑问是他最需要思考的东西,但也有很多平庸的问题需要考虑和处理。 “融资到位了吗?”“我的观众有足够的好座位吗?”“我在哪里可以弄到人类的头骨?”

我敢打赌,在莎士比亚的头脑中最不需要考虑的事情是:“这是文学吗?”

当我还是一个刚开始写歌的少年时,甚至当我开始因为我的能力而取得一定知名度时,我对这些歌曲的愿望也不过如此。我希望它们能够在咖啡馆或是酒吧听到,后来也许有像卡内基音乐厅,伦敦Palladium这样的地方。 如果我的梦想再大一点,也许就是我希望能制作唱片,在收音机里听到我的歌。那是当时我心中的大奖。制作唱片、在收音机听到你的歌,因为你可以获得很多听众,这样你也许就可以继续做你已经开始做的事情。

当然,现在,很长时间以来我一直在做我起初想要做的事情。在世界各地,我已经制作了几十张唱片,举行了几千场音乐会。 不过,我的歌曲才几乎是我做的所有事情的中心。它们似乎在不同文化的许多人的生活中找到了一个位置,我非常感谢。

但我必须说,作为一个表演者,我为50000人表演过,也为50人表扬过。我可以告诉你,为50人表演更难,因为5万人会形成一个单一人格,但50人不会。每个人都是一个个体,有独立的身份,一个自己的世界,他们可以更清楚地感知事物。你的诚实,以及它如何与你的天赋的深度相关联会受到考验。 诺贝尔委员会这么小,我没有忽略这个事实。

但就像莎士比亚,我也经常忙于努力追求创造性和处理生活所有方面的平庸事情。“谁是这些歌曲最好的音乐家?“我在合适的录音室录音吗?“这首歌的调子正确吗?”有些事情永远不会改变,即使在400年后。

我从来没有时间问自己一次:“我的歌是文学吗?”

所以,我真的感谢瑞典学院,既花时间考虑这个问题,并最终提供这样一个美妙的答案。

给大家献上我最好的祝福。

鲍勃·迪伦

演讲英文全文:

Good evening, everyone. I extend my warmest greetings to the members of the Swedish Academy and to all of the other distinguished guests in attendance tonight.

I'm sorry I can't be with you in person, but please know that I am most definitely with you in spirit and honored to be receiving such a prestigious prize. Being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is something I never could have imagined or seen coming. From an early age, I've been familiar with and reading and absorbing the works of those who were deemed worthy of such a distinction: Kipling, Shaw, Thomas Mann, Pearl Buck, Albert Camus, Hemingway. These giants of literature whose works are taught in the schoolroom, housed in libraries around the world and spoken of in reverent tones have always made a deep impression. That I now join the names on such a list is truly beyond words.

I don't know if these men and women ever thought of the Nobel honor for themselves, but I suppose that anyone writing a book, or a poem, or a play anywhere in the world might harbor that secret dream deep down inside. It's probably buried so deep that they don't even know it's there.

If someone had ever told me that I had the slightest chance of winning the Nobel Prize, I would have to think that I'd have about the same odds as standing on the moon. In fact, during the year I was born and for a few years after, there wasn't anyone in the world who was considered good enough to win this Nobel Prize. So, I recognize that I am in very rare company, to say the least.

I was out on the road when I received this surprising news, and it took me more than a few minutes to properly process it. I began to think about William Shakespeare, the great literary figure. I would reckon he thought of himself as a dramatist. The thought that he was writing literature couldn't have entered his head. His words were written for the stage. Meant to be spoken not read. When he was writing Hamlet, I'm sure he was thinking about a lot of different things: "Who're the right actors for these roles?" "How should this be staged?" "Do I really want to set this in Denmark?" His creative vision and ambitions were no doubt at the forefront of his mind, but there were also more mundane matters to consider and deal with. "Is the financing in place?" "Are there enough good seats for my patrons?" "Where am I going to get a human skull?" I would bet that the farthest thing from Shakespeare's mind was the question "Is this literature?"

When I started writing songs as a teenager, and even as I started to achieve some renown for my abilities, my aspirations for these songs only went so far. I thought they could be heard in coffee houses or bars, maybe later in places like Carnegie Hall, the London Palladium. If I was really dreaming big, maybe I could imagine getting to make a record and then hearing my songs on the radio. That was really the big prize in my mind. Making records and hearing your songs on the radio meant that you were reaching a big audience and that you might get to keep doing what you had set out to do.

Well, I've been doing what I set out to do for a long time, now. I've made dozens of records and played thousands of concerts all around the world. But it's my songs that are at the vital center of almost everything I do. They seemed to have found a place in the lives of many people throughout many different cultures and I'm grateful for that.

But there's one thing I must say. As a performer I've played for 50,000 people and I've played for 50 people and I can tell you that it is harder to play for 50 people. 50,000 people have a singular persona, not so with 50. Each person has an individual, separate identity, a world unto themselves. They can perceive things more clearly. Your honesty and how it relates to the depth of your talent is tried. The fact that the Nobel committee is so small is not lost on me.

But, like Shakespeare, I too am often occupied with the pursuit of my creative endeavors and dealing with all aspects of life's mundane matters. "Who are the best musicians for these songs?" "Am I recording in the right studio?" "Is this song in the right key?" Some things never change, even in 400 years.

Not once have I ever had the time to ask myself, "Are my songs literature?"

So, I do thank the Swedish Academy, both for taking the time to consider that very question, and, ultimately, for providing such a wonderful answer.

My best wishes to you all,

Bob Dylan